When I listened more closely, I could hear the unheard – the sound of flowers opening, the sound of the sun warming the earth, and the sound of grass drinking the morning dew (Kim, 1992, p.124)

Dean Berry cited that article when presenting Chan Kim the BCG Bruce D Henderson Chair of Strategy and International Management at INSEAD. The lessons have remained with me ever since reading it. And, in this piece, I wish to elaborate on the listening aspect of leadership – and how it relates to building the practice and the culture of the engaged university.

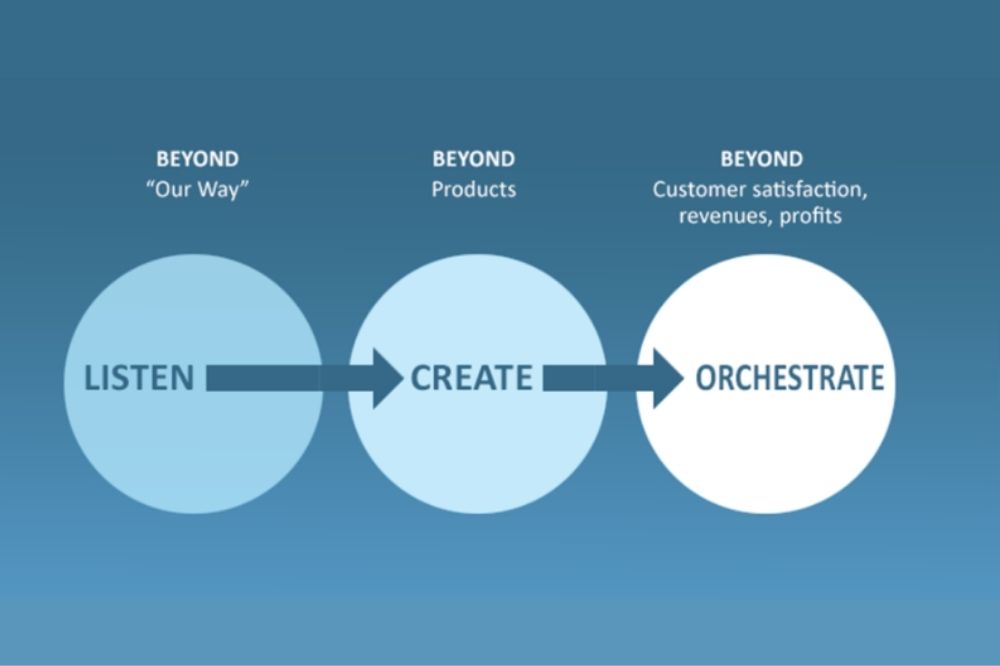

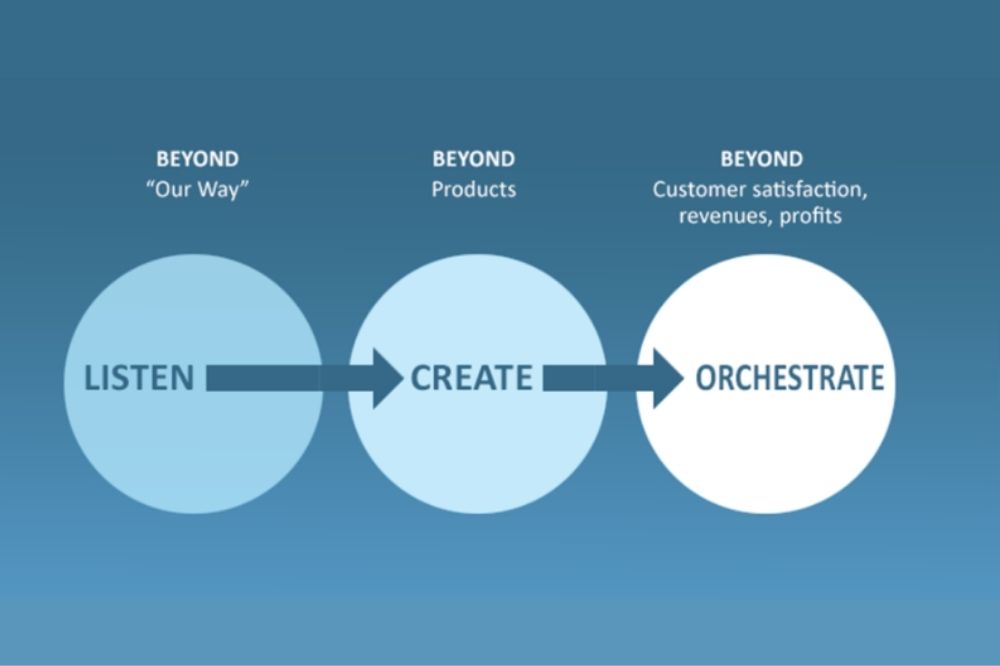

There can be no communication without listening to the other. There can be no engagement without listening to your counterparts and stakeholders. There can be no successful innovation without listening to your market and potential clients. That is why

‘Listen‘ is the first cog in our mechanism for generating powerful engagement momentum.

The general model is outlined in my previous article

(Leadership for the Engaged University: Nurturing Social Capital to Leverage Organisational). Now, we delve more deeply into the Listen mode. And we develop four broad categories of listening, along two axes.

However, before we go down that route, let us remember the momentum needs ongoing energy – it is iterative – and the listening

(an interactive activity) – should also be ongoing. This is not a linear, static process. It is dynamic. In the previous article, we also mentioned we should be humble while listening. At the same time, we can also feel proud and fulfilled by our engagement achievements and the meaning they bring to us and to our stakeholders.

To develop the

Listen mode of the model, I will briefly discuss ambidexterity in leadership. Then, I explain how humility helps to listen. That provides context for the ‘Insight Discovery Matrix’ : four broad categories, with important practical applications. Finally, I make a few high-level suggestions to help the engaged university – and its leadership – develop its listening capabilities.

The Ambidextrous Leader

There is a rich vein of research (Ulrich, Christian, Keld, & Ann‐Kathrine, 2018; Markides, 2007; Heavey, 2015; Tushman, 1996) and current

discussion on ambidexterity bringing together exploration and exploitation. That is reflected in the model being presented here.

Listen is the exploration element: discovering deep truths and motivations that drive behaviour.

Create is the exploitation element: executing on the research; bringing new knowledge to fruition.

Orchestrate is the binding element: culture and leadership that can generate, maintain and power the momentum effect for ongoing growth through engagement.

Humility: Discovery with an open mind

When embarking on an innovation project, the research mode is often exploratory. Even if the process is directly testing our hypotheses (and every new venture is akin to a hypothesis-testing experiment), we should be open to surprises. Hence, the open mind. Hence one form of humility – we listen to the facts.

We might observe unusual patterns. At least, they might be unusual to us. The black swan did not exist – for Europeans – until they saw it in Australia. At school, I was taught Australia, the country where I live, was ‘discovered’ by Captain Cook in 1770. Well, Europeans had been here before that. Oh, and the Indigenous populations had been here for much, much longer before that. Hence, it was not so much of a discovery in absolute terms. The knowledge existed already. It was part of others’ reality. Or perhaps the Europeans were the others? This reality is subjective, depending on who we place as the focus of attention. To be truly customer, or stakeholder, focussed, we must place them at the centre of attention. There might be one set of facts, but we all have our own personal realities. Others’ reality will likely be different from ours. This requires empathy. It requires being open to – and respecting – different perspectives.

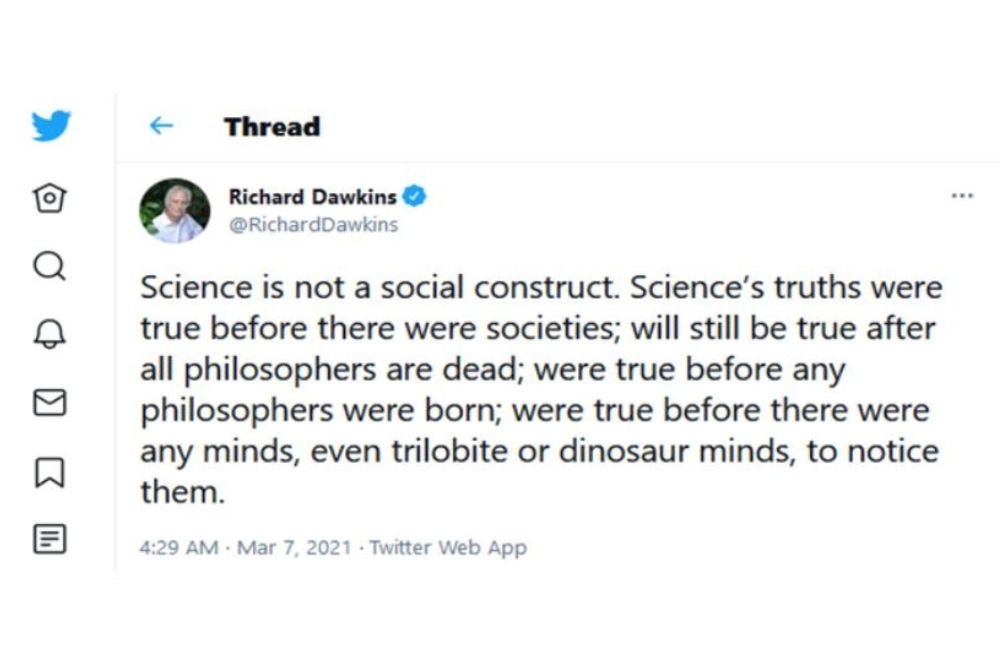

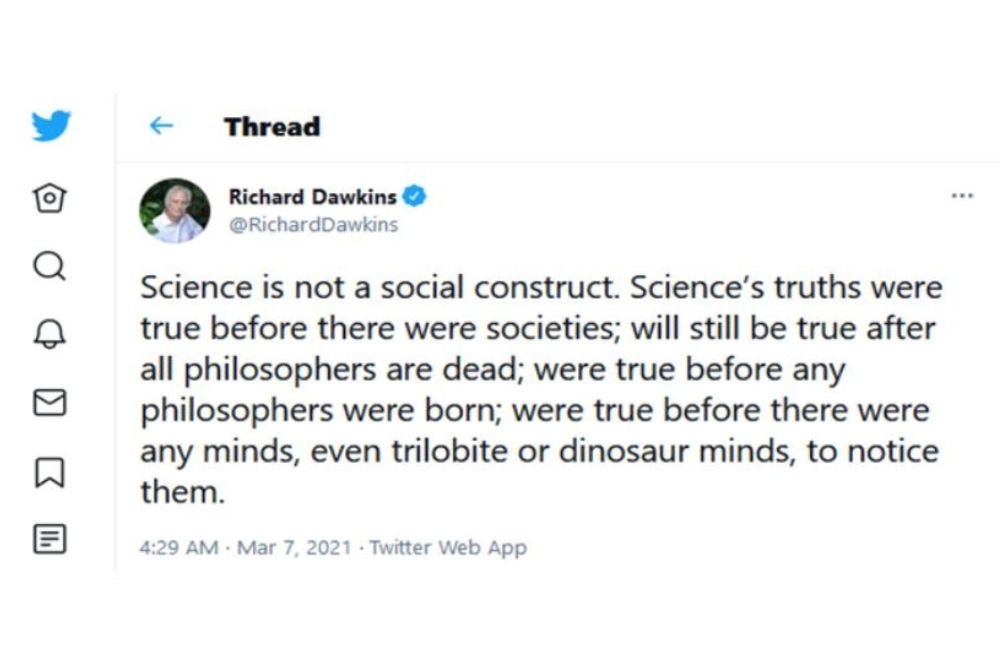

In fact, knowledge can develop in a bricolage manner, based on social context (Brown & Duguid, 1991). Recently, that concept generated considerable activity, following this Twitter post by Richard Dawkins:

Twitter post by Richard Dawkins

Twitter post by Richard Dawkins

To enact the open-mindedness I am promoting, we need to acknowledge our biases, and emotional and philosophical commitments (Eisenhardt, 1989; Huy, 2012; Jick, 1979; Markus & Lee, 2000).

We might not like what we hear. We might be so enormously enthusiastic about our innovation, our bright idea, our new initiative, but maybe nobody else cares anywhere near so much. Educators, researchers, and practitioners in the entrepreneurship and innovation field see that all the time. The innovation is often product-based, not customer-driven. It is something the innovator feels passionately inside themselves.

All that work you put into the project.

Nobody cares.

Need to start again.

Need deep re-designing.

(Research analogy: Reviewer 2 prevails.)

Perhaps your baby is ugly.

Dealing with all this requires much humility … and associated resilience.

Insight Discovery Matrix

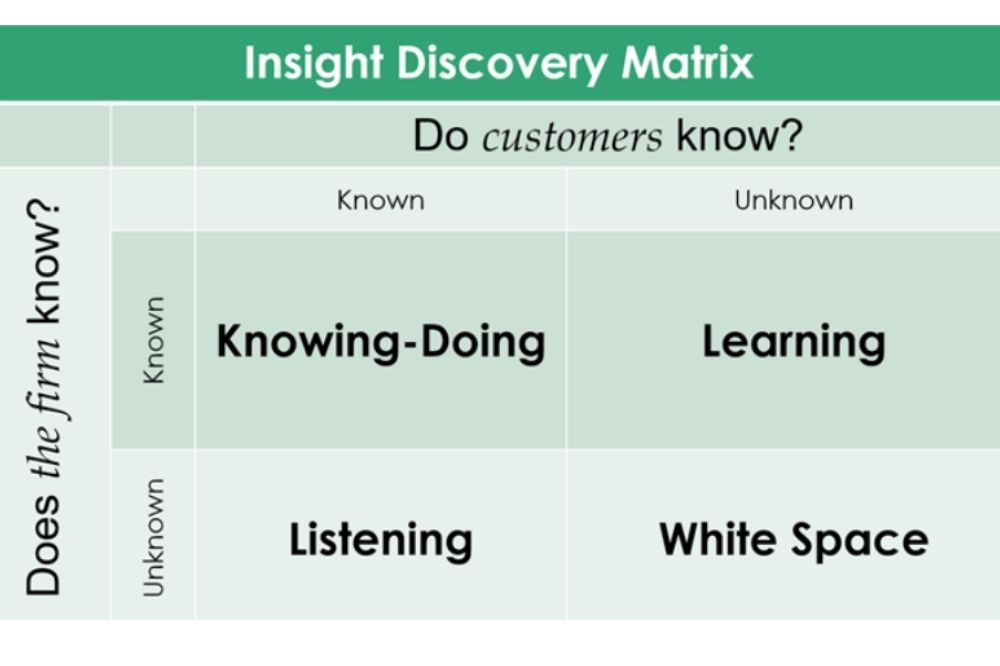

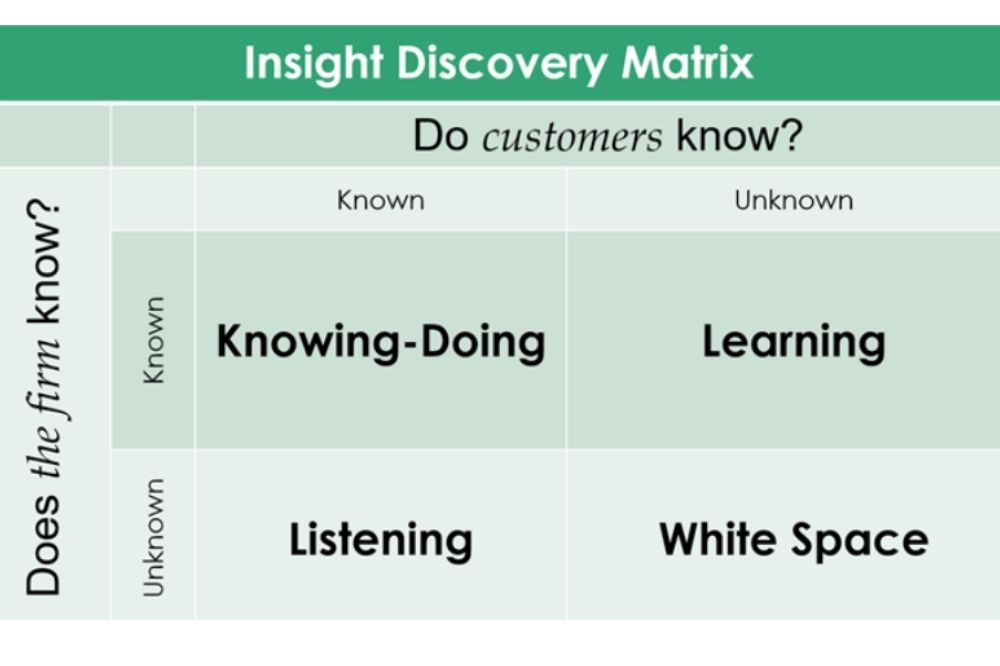

Here, I draw on the insightful work of Larréché (2008) that has strong connections with Blue Ocean Strategy (Kim & Mauborgne, 2004, 2019) and Blue Ocean Shift (Kim & Mauborgne, 2017). A nice 2*2 matrix helps us reduce complexity, initially. Then, we can delve more deeply into each quadrant. That brings nuance. It can lead down various routes for developing our engagement.

Our quest is: exploration and discovery of unfulfilled desires. Thus, it helps to posit the questions in terms of ‘What do we (not) know?’ and ‘Who knows?’

Source: (Larréché, 2008, p.2393)

Knowing-Doing

Source: (Larréché, 2008, p.2393)

Knowing-Doing

This seems very straightforward. Customers know what they want. We know what they want. Just do it! In fact, two basic impediments can interfere.

First, there might be internal corporate apathy.

‘The machinery is working well. We have so much to do. Why start another long, bureaucratic process?’ (and we know universities are strong on bureaucracy.)

Second, the technology or processes might not exist to implement what we all know to be desirable. Just think of all the options we have today but were not available a decade ago. (I was an outlier during my undergraduate days because I would type my essays – on a typewriter – rather than submit handwritten!)

Engaged universities have a dual relationship with this quadrant. First, we need to overcome our own internal inertia. Second, we develop new knowledge and process technology that satisfies the unfulfilled desires.

Learning

In these cases, the firm knows what customers want, but the customers don’t. That sounds contradictory – and the opposite of the humility I mentioned above.

Well, we all know people want better lifestyles: health, environment, etc. But, most lack full knowledge to optimise their context. In this quadrant of the matrix, the firm knows of solutions that would improve customers' wellbeing. That information just has not reached the community yet. Hence, we have a straightforward education or information task.

At the time of writing, the Covid-19 vaccination was a hot topic. There was much confusion in the community about safety and efficacy. That is an extreme example of the task for this type of insight discovery.

Engaged universities can certainly take stock of this – and contribute to solving the problem. More mundane education tasks can be to bring their capabilities to marginalised groups. These are groups that are less likely to know or understand how universities work. They are less likely to have social access, to have role models who have taken paths into higher education or research. Fulfilling their needs contributes to society. Just as important, the new capabilities developed can be deployed at large.

Further, meaningful science communication – and that requires understanding social and political dynamics, as well as story-telling – adds to wellbeing. Here, a sole focus on STEM is problematic. A range of disciplines should be brought to bear, with all their complementary assets (Teece, 1998).

Engaged universities should include an education component in their research or consulting projects for/with external partners – helping the partner/client understand better the value and applications of the project outputs.

Listening

The beautiful Parables of Leadership (Kim & Mauborgne, 1992) encourage us to listen deeply, to the unspoken word. In a worldlier business sense, it relies on having good sensing mechanisms (Doz, Santos, & Williamson, 2001) to pick up weak signals – before others do.

There is strong research and practitioner literature on this, from von Hippel’s lead user approach (von Hippel, Thomke, & Sonnack, 1999), to Porter’s demand conditions in the clusters model (Porter, 1998), and strategic agility (Doz, 2020).

We all now know of millions of young people demonstrating around the globe. They have deep concerns about climate change. That creates enormous opportunities for business, research, and policy development. Anybody who was listening earlier would have an advantage – in time, at least – over those who remain closed to the new realities.

Source

Source

In practical terms, looking for advanced users and/or looking at how marginalised groups deal with problems can bring important insights. For example, designing products and services for people with disabilities can make them also much more desirable for the population in general (e.g. because easier to operate.) Following artists or other groups who move into certain quarters of your city can lead to improved living environments.

Engaged universities, again, can have a dual relationship with this quadrant. By being connected – engaged – with industry and society at large, should be able to sense the weak signals early.

On the other hand, we are typically at the forefront of new ideas. The climate change challenge is hardly new in the research world. It has simply reached deeper awareness in the community. So, engaging in more effective science communication, engaging better in the social, political discourse will help our breakthrough discoveries to be absorbed and implemented.

White Space

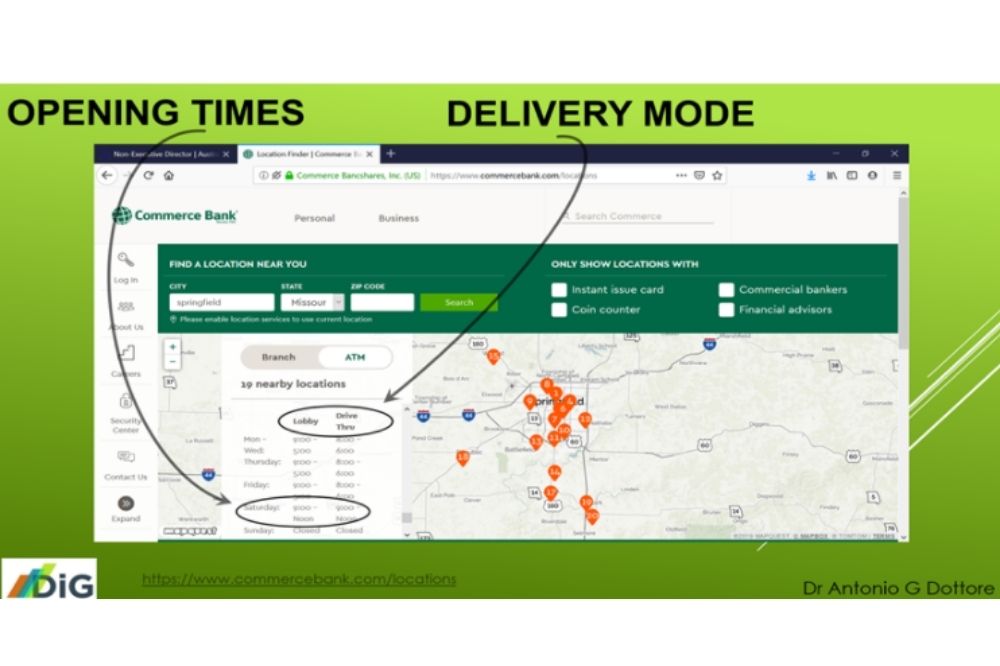

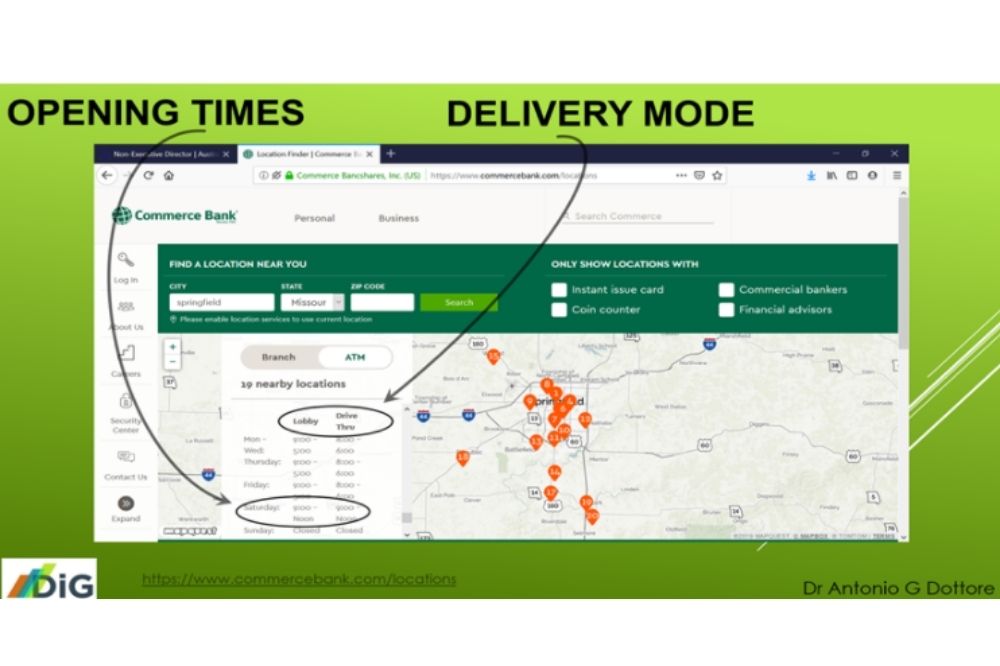

The unknown unknowns are there to be discovered. As a child, I would go to my local bank branch, with a passbook in hand. There was no concept of banking by phone. There was no concept of the internet, let alone internet banking, mobile banking, fintech. These advances generally work well. I am very happy using

Wise (previously

Tranferwise ) for sending money internationally: very easy, very fast service, very good customer interaction. Then again, there might be cultures where other methods work just as well (note the drive-through option):

Engaged universities

Engaged universities are crucial for this quadrant. Here, the future is most fluid and fuzzy. Think tanks, research institutes help develop these futures. This is where society can benefit most from our engaged approach. Think tanks, direct engagement with decision-makers and influencers are among the obvious remedies.

Here is an example of how this can work. In Australia, Co-operative Research Centres (CRCs) are intended to bring together research institutes and the community at large. They require positive interest – with contributions in money and in-kind – from industry partners. I was appointed to the Interim Board of a CRC on

Longevity. It brings together eight universities and over eighty industry partners. These can be for-profit companies, but also local government, not-for-profits, and industry associations.

The topics of living longer, living better, the economic and social drivers and consequences of greater longevity are deeply important. This (the CRC model) is one form of

engaged universities forging the white space future.

Practical Implications

There have been direct implications drawn for each quadrant above. Here, we make some broader suggestions that also apply to the engaged university.

ONE: Listen. Listen. Listen. However, there are many ways of listening, and observing our context leads to generating knowledge. As researchers, we (should) understand this.

TWO: Develop a variety of sensing devices. That includes being a customer of your own service: eating the same meals you serve to aged care residents; taking out a mortgage in your own bank; enrolling in a course at your own university.

THREE: It’s best if senior staff are actively involved, directly ‘get their hands dirty’, in the trenches. That is psychologically and strategically valuable:

- Staff observe the commitment is real vs bland statements that are easily forgotten

- Builds the engaged culture with repeated, observed action

- Easier for senior staff to absorb the lessons having been directly involved in generating and analysing the data

Bibliography

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovating. Organization Science, 2(1), 40-57.

Doz, Y. (2020). Fostering strategic agility: How individual executives and human resource practices contribute. Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100693. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100693

Doz, Y. L., Santos, J., & Williamson, P. J. (2001). From global to metanational: How companies win in the knowledge economy (hardcover). Boston: Harvard Business School Press Books.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

Huy, Q. N. (2012). Improving the odds of publishing inductive qualitative research in premier academic journals. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 48(2), 282-287. doi:10.1177/0021886312438864

Jick, T. D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 602-611.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2004). Blue ocean strategy. Harvard Business Review, 82(10), 76-84.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2017). Blue ocean shift: Beyond competing. Proven steps to inspire confidence and seize new growth.: Hachette Books.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2019). Nondisruptive creation: Rethinking innovation and growth: It's time to dispel the myth that innovation must be disruptive. Nondisruptive creation is an alternative path to growth. MIT Sloan Management Review, 60(3), 46-55.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. e. A. (1992). Parables of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 70(4), 123-128.

Larréché, J.-C. (2008). The momentum effect: How to ignite exceptional growth. New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing.

Markus, M. L., & Lee, A. S. (2000). Special issue on intensive research in information systems: Using qualitative, interpretive, and case methods to study information technology -- second installment; foreword. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 1-2.

Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 77-90.

Teece, D. J. (1998). Capturing value from knowledge assets: The new economy, markets for know-how, and intagible assets. California Management Review, 40(3), 55-79.

Ulrich, K., Christian, K. H., Keld, L., & Ann‐Kathrine, E. (2018). Experience matters: The role of academic scientist mobility for industrial innovation. Strategic Management Journal. doi:doi:10.1002/smj.2907

von Hippel, E., Thomke, S., & Sonnack, M. (1999). Creating breakthroughs at 3m. Harvard Business Review, 47-54.